-

GovernanceMay 12, 2022

The 23rd Session of Parliament: Political Infighting and Piecemeal Solutions in an Unprecedented Crisis

- Nermine Sibai

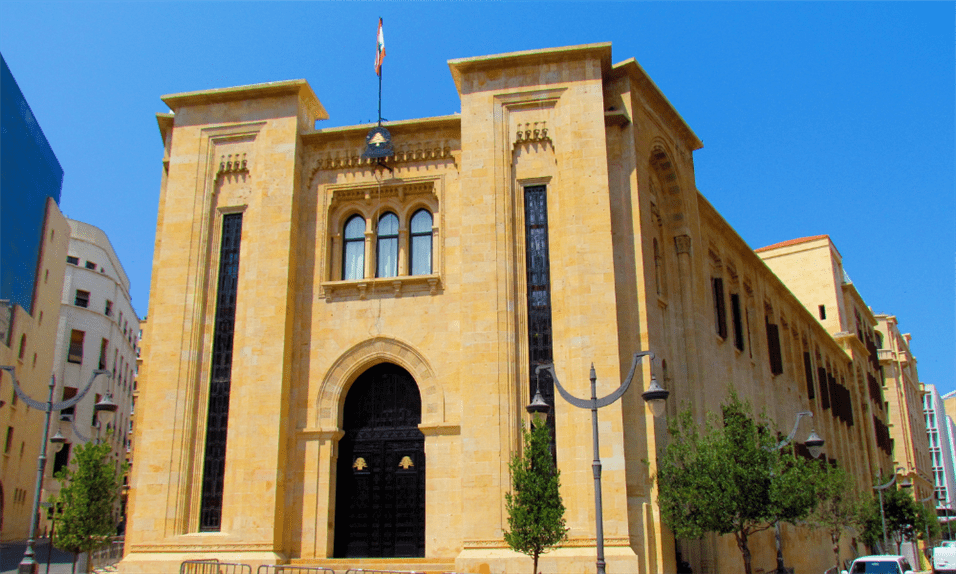

Source: Flicker

Source: FlickerThe 23rd session of the Lebanese Parliament has finally concluded with the election of a new legislature on 15 May 2022 [1]. In the fall of 2019, a little over a year after the last parliamentary elections, the Lebanese economy began to seriously falter, ushering in some of the most difficult years in Lebanon's modern history. In fact, multiple successive crises have taken place during the mandate of this parliament, including a massive popular uprising against corruption, an unprecedented economic and financial crisis, a global pandemic, and the devastating explosion at the Port of Beirut.

This text is part of a public policy summary that will be published soon. It addresses the performance of this parliament by assessing its quantitative and qualitative productivity during its four-year term [2]. As such, we will not delve into the legislative effectiveness of the last parliament—by analyzing numbers and the quality of the approved laws—given the nature of these problems, which is outside the scope of this article.

However, we have decided to shed light on the most prominent problems that weaken parliamentary work in the context of its oversight and legislation functions. We aim to inform public opinion about the institutional challenges and the various arguments that are invoked to obstruct the parliament's work. In short, we are addressing those who seek to reform the work of parliament, including members of parliament (MPs), candidates, and civil society organizations involved in restoring the role of parliament and putting it back on the right track.

Politicizing Parliament’s Oversight Role

“They obstructed us, they did not let us work!” This is the most common excuse you hear from state officials, blaming each other for their poor record in office. Lebanon’s consociational (“power sharing”) political system effectively paralyzes efforts towards any serious accountability of governments by parliament. Consensual governments are like a mini-parliament, in which all the parliamentary blocs are represented. Therefore, questioning the government and holding its ministers accountable is viewed as conflicting with the National Pact (al-mithaq al-watani), which has become more sacred than the constitution itself. It also depends on the whims and personal interests of the blocs that vary according to circumstances. In fact, some representatives complain that they are unable to pressure ministers to implement laws, respect deadlines, answer their questions adequately, or even appear before committees. Questioning a minister can quickly become overly personalized and viewed as an insult rather than a routine political process.

This problematic is manifested in many of the MPs speeches or interventions during the 23rd legislative session—new in context, but old in content. For example, during the only question-and-answer session of 2019 [3], when the government was asked about its neglect of the agricultural sector, MP Georges Okais said: “The government’s response, Mr. Speaker, contains a clear answer to one of the eight items. Answers to the other items were very general and not backed by any documents, data or numbers.” In the same context, and during the same session, commenting on the government’s answer to his question about environmental pollution on the Jounieh sea road and in Kesrouan [4], Representative Farid Haykal Khazen said, “The government’s answer was all intentions and promises but no actions. They claimed, ‘We tried to do this, and we wanted to do that, and we will try to do this...’”

One of the most prominent examples of disregard for accountability was the withdrawal of the minister of environment from the session, prompting the prime minister [5] to committing himself to answer on behalf of the minister, but failed to do so. In fact, when MP Osama Saad asked a question about the Sidon waste processing plant and the measures taken by the ministry of environment to limit its damage, the prime minister replied: “Mr. Speaker, the minister of environment is not here. I will not be able to answer this question. We will answer your question during the next session hopefully.”

MP Hassan Fadlallah then replied: “Mr. Speaker, given that we can ask questions, after the written ones, all members of the government should be present."

The Speaker: “Exactly.”

Fadlallah: “Presence should be mandatory to all ministers...”

It goes without saying that the prime minister and the ministers of all the blocs are responsible for the government’s negligence, but the parliament itself also bears a great deal of responsibility for the leniency it shows in its oversight function, for politicizing it, and subjugating it to narrow interests.

Budgets Without Expenditure Reports

The clearest evidence of the lack of accountability is the flagrant and continuous constitutional breach [6] of government handling of public finances, as parliament has failed to get government to issue an expenditure report, which accounts for its financial expenses for this session and other sessions since 2005 [7]. It is legal common knowledge that budgets cannot be approved without an expenditure report. In this session, like others before it, parliament still allows spending on the basis of the twelve-month rule. In turn, the government is still not concerned about deadlines for sending budgets for approval to parliament, and it does not abide by the prerequisite of passing the law of expenditure reports of the past years [8]. Confidence was not cast in any minister or government in light of these fundamental breaches, and consensus on “patchwork solutions” is still the dominant position among all.

Complacent Governments with Minimal Oversight

Article 136 of the rules of procedures of the parliament states that an oversight session, both ordinary and exceptional, should be held after every three working sessions at most. [9] While this fundamental rule is constantly violated, representatives turn a blind eye and governments are happy with the leniency.

Parliamentary observers are aware of the extent to which the majority of previous legislatures since the Taif agreement have been deprived of any real ability to correct government performance. They also witness the adherence of most representatives and ministers to the “internal kitchen,” system instead of seriously objecting to violations through legal and constitutional instruments, and in line with the parliaments’s procedures of work.

In this context, we recall the latest session of confidence cast in Minister of Foreign Affairs and Emigrants Abdullah Bou Habib, which should have been held on 4/28/2022. The request to hold this session came from the Strong Republic bloc [10], but the session did not take place because the parliamentary blocs made sure the session’s quorum was not met [11]. This was the first time a minister is subject to a vote of confidence cast without even being questioned, in a precedent that was the first of its kind [12]. However, this was no surprise given the context—a wide-open electoral struggle between the various blocs a few days before the diaspora voted in elections occurring after a very critical phase in the country. In fact, an entire city exploded, the whole financial banking system collapsed and people's life savings vanished; yet never once in this legislative session, has a meeting been held to cast confidence in a minister. However, the mere suspicion of crooked procedures and the possibility of losing some electoral votes was enough to expedite the submission of such a request. The reaction of the Speaker of Parliament, Nabih Berri, was even faster. He received the request and quickly set a date for a session in a vote of confidence in a minister who would serve only a few days in a government that will cease to exist after the parliamentary elections. This confirms once again that parliamentary work is based largely on political rivalries and narrow calculations, and not on legislation and proper oversight that cares for peoples’ rights and needs [13].

Unfortunately, parliamentary work takes place behind the scenes and not through proper parliamentiary procedures, as required by law. The statement of Representative George Adwan after the confidence vote session was adjourned is the best proof of this. He asked the people to respond at the polls, saying: “It is not important to vote for confidence in parliament, but rather in the elections.” The situation will remain unchanged as long as the ruling power favors the establishment of a consensual system based on mutual quotas instead of establishing sound democratic systems. We believe that, in the context of the sectarian system based on clientelism, the rule of the majority and the opposition of the minority becomes an urgent need. There will be no real accountability without the separation of powers. As long as the MP is a minister, especially in the context of the divisions between the blocs. And as long as the solutions are always based on parallel settlements, accountability will remain a formality that lacks seriousness.

Chaotic and Discretionary Legislation

The parliament has a public committee made up of all representatives who discuss laws and vote on them, a parliament bureau that organizes the administrative work of the public committee, and various other committees [14] that prepare and study the texts in-depth. Each of these three bodies and their working mechanisms suffer from structural irregularities and gaps that must be corrected by amending the internal system of the parliament to improve transparency and, consequently, enhance peoples’ participation in the legislation and oversight process.

The parliament’s bureau and its chairman receive and record proposals and bills, and transfer them to the relevant committees for study. However, it turns out that the administrative structure of this bureau lacks the necessary mechanism to control this process. According to Article 102 of the rules and procedures, “the Speaker of Parliament shall refer the law proposal to the relevant committee or committees and submit it to the government for review, unless the rules set special regulations.” Article 109 states, “The Speaker submits the expediated proposal or project to the Parliament during its first session after the submission, even if it is not on the agenda.” This gives the members and the president of the bureau the opportunity to have discretion in referring the submitted proposals (or burying them), which promotes chaos, and consequently, slows down the process of studying texts and approving legislations.

At the level of the public committee, we note that some of the information is not included in the committee’s minutes of meetings, as stipulated by the rules of procedures. The public character of the committee should ensure that every citizen be informed of the course of the sessions, the extent of the MPs participation, and what their positions are; much like the purpose of adopting the principle of voting by show of hands, and then calling out names [15] to find out who voted for or against the laws. However, the lack of regular documentation in the minutes (only writing majority/the article was ratified or minority/the proposal was rejected), and the absence of mechanisms that allow direct follow-up of the sessions, renders the public character void and information is withheld from those wishing to follow up on the performance of MPs that would allow them to make informed decisions when choosing them. The least we can say about the voting and documentation process is that it is still primitive from a logistical point of view, and it is inconceivable that digital technology has not been used yet to organize the legislative and monitoring process.

In addition, parliament adopts the principle of confidentiality of the committees’ meetings, and this matter is automatic unless the committee decides otherwise, as stated in Article 34 of the rules of procedures of the parliament [16]. Accordingly, its minutes remain confidential and each committee issues final reports only about the laws it has studied, without mentioning the deliberations, the participation and the positions of members of the parliamentary committees. A number of representatives have submitted proposals in the past sessions to amend the rules and procedures to address this matter, but parliament has been unable to study and approve them so far—thus, none of them has been referred to a specialized committee for study or put on parliament’s agenda. In past years, many requests have been made from outside parliament to render the committee meetings public. The current 23rd legislative session saw the peak of these demands for transparency and immediate accountability, with the October 17 uprising and its aftermath, in the context of the deterioration of trust between the people and the constitutional institutions, especially when it comes to financial and economic issues. Fighting corruption and holding the corrupt accountable became one of the basic demands in order to preserve what was left of the state.

In light of the popular pressure on the streets, and from the international community to carry out real reforms, in return for financial support, MPs focused on presenting draft laws. Among these are capital control, public procurement, bank secrecy regulations, independence of the judiciary, competition reforms, and combating corruption. Laws were also dug up and amended, such as the Stolen Funds Recovery Act, the law against corruption and illicit enrichment, and the establishment of a National Anti-Corruption Authority. Despite all of this, most of these laws were not approved, particularly the capital control law. Those that were approved were either rendered ineffective before being passed or approved but have yet to be implemented. As such, the majority of parliamentary activity during this session was a big show without any tangible results on people’s lives. The economic situation worsened, and the financial and social situation deteriorated further with the spread of the Coronavirus pandemic. As a result, the national currency continues to lose its value day after day.

Legislation Far from People's Needs

In light of oversight inaction and legislative chaos, people’s concerns and basic needs are absent from the discussions of parliament. In this context, MP Paula Yacoubian described the situation in one of the legislative sessions very clearly [17]: “We seem to be so out of touch with the reality in Lebanon. Today, I understand your decision, Mr. Speaker, to ban political speeches and suspend the incoming papers, but I do not understand how a parliament cannot speak about politics, and directly discusses laws. Representatives have the right today to express the voice of the people. If you are hiding certain disagreements, I urge you to let it go, for it is better to let the disagreements out than to feel like everything has already been settled outside this parliament and we are only here to raise hands. I urge you, Sir, to let us know what the political problems and considerations are. Outside these walls, fear of starvation reigns, so with all due respect to all topics, we are here today legislating issues that are out of touch with peoples’ reality, their fears and worries. There are some laws related to the reduction and cancellation of taxes and fees.” In the same context, and within the same session, MP Simone Abi Ramia said: “I am talking about the issue of the incoming papers. We attend legislative sessions several times and hear the representatives talk about issues concerning their regions and about public policy. All I was asking for is to hold a meeting every two weeks dedicated to public policy where we vote on laws and conduct our legislative duty. And when we want to speak politics and hold the government accountable, we would have sessions for this matter.”

Legislation on Demand

The main issue is the absence of an integrated legislative policy, especially with regard to substantive life issues. The parliament’s approach is almost always piecemeal, and often deals with people’s rights in a scattered and contradictory way. The “general amnesty law” is but one example of this approach, in addition to a stream of amendments to the penal code, in the complete absence of an integrated and comprehensive vision of the country’s penal policy. Parliament introduced the proposal of a general amnesty law on the agenda of the first legislative session on 12 November 2019 [18]. However, it was upended by street protest, after it became clear that there are certain political groups benefiting from this law, which did not come within the framework of a system aiming to establish justice. Rather, its primary goal was electoral and political, far from any real social reform.

Instead of reforming prisons, speeding up judicial trials, and working to pass the law on the independence of the judiciary, parliament insisted on re-introducing it on the agenda over and over again [19]. As for the penal code, the recent amendment of some articles of the law, whereby “some penalties have been replaced by free social work” is a good example of the above [20]. In the same legislative session, Representative Samir Al-Jisr stated the following: “I have an objection to the whole principle; when it comes to form, it was not added as a chapter of the Penal Code, it has become like an independent law. This creates confusion in the implementation process when laws are distributed.”

Accordingly, the weak performance of parliamentary work is due to many reasons that can be summed up as follows: 1) The nature of the sectarian-consensual political system, the quality of the electoral law in force, and the “unhealthy” relationship between the legislative and the executive branches of government, 2) The second reason is technical, related to the structure of parliament and the lack of clarity in the mechanisms and procedures applied by its bodies, and 3) The absence of a legislative vision and experience among the majority of representatives, and their preference for providing services to their supporters. All of these matters naturally affect the productivity of the legislature and quality of legislation, on the one hand, and the effectiveness of the government oversight role of parliament, on the other. The main recommendation we offer to reformist parliament members is to insist on promoting a sound legislation and oversight function of parliament, instead of turning it into a platform where the various parties compete to pass laws that serve their narrow interests.

[1] The twenty-third session (23rd) began in May 2018 and ended on May 16, 2022.

[2] It should be noted that we had previously published a comprehensive study on parliament’s performance in the 22nd session, entitled “The Lebanese Parliament 2009-2017: Between Extension and Paralysis - A Roadmap to Restoring Parliament’s Legislation and Oversight Roles.”

[3] A question-and-answer session in the first regular session on 4 October 2019, during which 13 questions were asked by 7 representatives only.

[4] The question was directed by MPs Farid Haykal Khazen and Chamel Roukoz.

[5] PM Saad Hariri.

[6] Article 87 of the Constitution: “The final financial accounts of the administration for each year must be submitted to the parliament for approval before the publishing the budget of the following year.”

[7] The last budget report to be approved was in 2005, for the year 2003.

[8] Article 83 of the Constitution: “Each year at the beginning of the October session, the government shall submit to parliament the general budget estimates of state expenditures and revenues for the following year. The budget shall be voted on article by article.”

[9] Article 136 of parliament’s rules and procedures: “After every three working sessions at most, ordinary and exceptional, a session is dedicated to questions and answers, interrogations or general discussions, preceded by a statement from the government.”

[10] The Lebanese Forces bloc submitted a request for an urgent session of parliament to hold the minister of foreign affairs accountable on grounds that he restricted the right of Lebanese expatriates to vote.

[11] Only 53 representatives out of 128 attended.

[12] According to the minutes of the parliament, the secretary-general of parliament said: “Never has a session of that kind been held neither before nor after Taif.”

[13] The National News Agency citing Al-Liwaa newspaper: “Bou Habib survived, but trust between allies did not make it!”

[14] 16 permanent committees and special, subsidiary, and joint committees

[15] Article 81 of parliament’s rules and procedures stipulates: “Voting on bills takes place article by article by show of hands. After voting on articles, the issue as a whole is put to vote by roll call.”

And Article 85: “The vote of confidence is conducted through the roll call procedure, by answering with one of the following words: confidence, no confidence, abstaining. The number of abstaining votes is not taken into consideration when calculating the majority.”

[16] Article 34 of Parliament rules says: “Committee sessions, work, minutes, discussions, and voting are confidential, unless the committee decides otherwise.”

[17] Legislative session on May 28, 2020.

[18] Then it was introduced in the session on 19 November 2019, and it was voted down again.

[19] Re-introduced on the agenda on 22 April 2020.

[20] Adopted in the legislative session on 26 June 2019.

Nermine Sibai is a lawyer and legal researcher in the field of human rights and public freedoms. Her work is focused on the protection of socially marginalized groups and those subject to discrimination. She holds a law degree from the Lebanese University and a master’s degree in private law. She also holds a bachelor’s degree in Business Administration from the American University of Beirut.