-

EnvironmentFeb 19, 2026

Lebanon’s Wastewater Sector: A Path to Development and Sustainability

- Nadim Farajalla

This reform monitor is supported by the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Beirut. The opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the donor.

What Is the Issue at Hand?

Lebanon’s wastewater sector has long faced scrutiny and criticism, with its deficiencies directly reflected in the nation’s deteriorating water resources. Numerous scientific assessments confirm the scale of the challenge. A 2024 study by El Chamieh et al., examining ten of Lebanon’s main rivers, found that 60% contained E. coli levels above permissible limits, while 40% exceeded FAO criteria for fecal coliforms in irrigation water.

Similarly, data from the National Council for Scientific Research (CNRS) in 2023 revealed that more than one-third (38%) of monitored coastal bathing sites were classified as polluted. These findings illustrate a national reality in which rivers, coastal waters, and aquifers are increasingly exposed to untreated or partially treated wastewater, solid waste residues, industrial discharge, and agricultural runoff.

Understanding how Lebanon arrived at this point requires revisiting its post-war trajectory. After the civil war ended in the early 1990s, reconstruction priorities were shaped by urgent demands for basic services. Potable water supply was positioned as the primary national concern, while sanitation and wastewater management were dealt with through partial measure. This decision had long-term consequences. The wastewater sector received far less investment, and institutional development lagged behind that of water supply services.

Policy and Institutional Framework

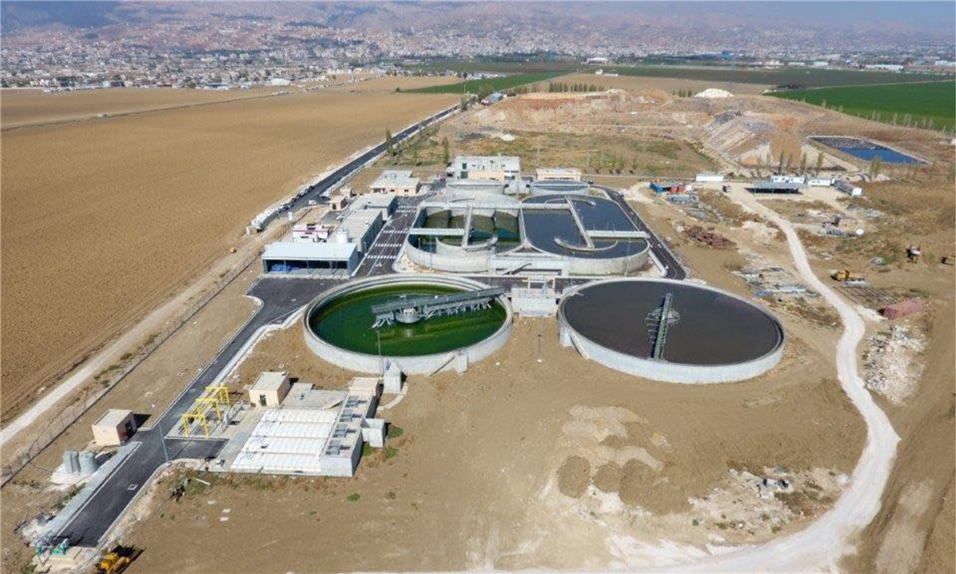

Nowhere was this imbalance more evident than in the Coastal Pollution Control Program (CPCP), launched with international support in the late 1990s. The CPCP led to the construction of major wastewater treatment plants along the coast and the development of primary networks intended to capture urban wastewater flows. Yet the program’s implementation revealed fundamental gaps. Mandates among three key entities—the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR), the Water Establishments (WEs), and municipalities—were poorly defined.

As a result, assets were constructed but not fully connected. Treatment plants operated below capacity or never reached adequate treatment levels. Municipal networks often remained incomplete, and the CDR continued to hold responsibility for operations and maintenance well into the 2000s and 2010s, even though legally the WEs were meant to assume these roles. Institutional fragmentation and unclear accountability mechanisms ultimately meant that infrastructure did not translate into effective service delivery.

Positive Developments and Remaining Challenges

Over the subsequent two decades, the wastewater sector remained underfunded, heavily donor-dependent, and insufficiently staffed. The financial collapse of 2019–2020 intensified these structural weaknesses. Electricity rationing disrupted pumping and treatment operations, forcing WEs to rely on expensive privately or institutionally owned diesel generation.

With revenues practically non-existent due to currency collapse, WEs struggled to cover basic consumables, chemicals, and spare parts. Many service providers accumulated arrears, and private operators responsible for O&M contracts found themselves unable to continue without government payments. The crisis jeopardized the continuity of wastewater treatment functions and created a real risk of system-wide failure.

Recognizing the public health and environmental implications, the Ministry of Energy and Water (MoEW), in partnership with international donors, stepped in to prevent collapse. A sector recovery roadmap was prepared, and crucial EU funding was mobilized through UNICEF between 2022 and 2023.

This emergency intervention proved vital. It ensured the continued operation of major wastewater treatment plants and key lifting stations, provided fuel and essential consumables, supported WEs with engineering expertise, and reinstated monitoring and reporting mechanisms that had been suspended since 2019. Most critically, it restored WEs as the legitimate operational managers of the sector, reinforcing the institutional pathway envisioned in national laws.

By 2025, data show that approximately half of Lebanon’s total wastewater treatment capacity had been reactivated to varying levels. Some plants were operating at preliminary or partial treatment stages, while others achieved improved efficiency compared to preceding years. This stability period also contributed to notable institutional gains: WEs began establishing resolute wastewater units; coordination between MoEW, CDR, WEs, and donor agencies improved; and systematic data collection resumed. These developments represent an important shift from past fragmentation toward a more coherent national wastewater management system.

Recommendations

Stabilization alone cannot deliver long-term water quality improvements. The sector now confronts the challenge of transitioning toward sustainable, integrated wastewater management. Several prerequisites have been identified:

- Establishing formal wastewater departments within each WE.

- Recruiting trained engineers and operators.

- Integrating wastewater tariffs into billing systems to support financial sustainability.

- Securing preferential electricity tariffs for WEs to reduce energy burdens.

- Incorporating renewable energy into facility operations.

- Reusing treated wastewater to improve water supply.

- Developing a national sludge reuse and disposal framework.

- Harmonizing Water Law 192/2020 with Municipal Law 118/1977 to eliminate governance ambiguities.

- Launching capacity development programs and standardized certification systems to professionalize the sector’s workforce.

Why Is This Important?

Lebanon’s wastewater sector is therefore at a critical juncture. The foundations of recovery are in place, supported by significant investments, enhanced institutional coordination, and renewed operational capacity. Yet the path forward depends on sustaining reform momentum, implementing structural changes, and ensuring stable financial and energy frameworks. With strategic planning and sustained political will, wastewater management can evolve from an environmental liability into a driver of public health protection, ecological restoration, and circular-economy innovation.

References

CNRS-Lebanon – National Centre for Marine Sciences. Annual Coastal Water Quality Report (latest release 2025). Beirut: CNRS.

El Chamieh C., El Haddad C., El Khatib K., Jalkh E., Al Karaki V., Zeineddine J., Assaf A., Harb T., Sanayeh E. B. “River water pollution in Lebanon: the country’s most underestimated public health challenge.” Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, vol. 30, no. 2, 2024, pp. 136-144.

Nadim Farajalla is the first Chief Sustainability Officer at the Lebanese American University. Formerly, he worked as a senior scientist and environmental engineer in the private sector, contributing to water resources, environmental impact studies, and climate resilience projects across the Middle East. He founded and led the Climate Change and Environment Program at the American University of Beirut’s Issam Fares Institute. His research addresses climate change impacts on human settlements, impact of climate change on security, the nexus of water-energy food, implementing Agenda 2030 in Lebanon and the region, and integrating sustainability in academic settings.